Ten years ago I was living in New York as a dance student, slowly consuming my savings, thinking the city might as well make or break me. Life meant survival in the concrete jungle with subway monsters and strange hormonal shifts. That year yoga went from something I was dabbling in to something that anchored me in my every day hustling and bustling. Ever since that time, yoga has been an irreplaceable constituent of my daily life. Now, that might sound nice, but actually for the last ten years, I have been obsessing about my practice more than I like to admit. The first phase, I thought it was imperative to get in a 90 minute Asana practice every day. The second phase, I added doing a 45 minute Pranayama practice every morning to the mix of expectations. And I actually did that religiously for over three years. Then, third phase, I had moved to Taiwan and had a lot of time on my hands, so my inner critic decreed I should do 30 minutes of seated meditation every morning. Which I did.

It only just occurred to me yesterday, that I have now spent the last ten years obsessing about how much was only just good enough and guilt-tripping when I didn't meet my lofty goals. Over the last two years of motherhood, this was more often than not. Yesterday, for the first time, I had to ask myself: Why? Why would I torture myself with all these expectations wrapped in a thick layer of guilt? And for ten years! Why? It suddenly dawned on me that this feeling of constraint is blocking my practice more than it is evolving it. I don't know how it is for you, but I don't like to be forced. Least of all by myself.

I was recently introduced to the concept of the lizard brain. This is the primitive oldest part of our brain responsible for survival instincts, such as fight, flight, fear, freezing in the face of danger and fornication. When we are reluctant to do something, it is usually because our lizard brain has smelled danger or disruption of a peaceful state. This part of the brain doesn't distinguish between the danger of running from a lion in the wild or the “danger” of getting yourself to move your tired body for a full 90 minutes, when it would be much more comfortable to lounge on the sofa. Both seem like threats to the lizard brain. And because it is well connected to its buddy, the logical thinking, excuse-making brain, we come up with all kinds of reasons why we should put it off and procrastinate: There's not enough time anyway, we have a cold or we are recovering from one, we had too much for lunch, we had too little and should get a snack first, we should return this call or reply to that email, we need to hit the snooze button one more time because we have been sleeping poorly lately... Right. We've all been there.

It's a cat biting its tail. The more we try to force ourselves to do it – practice, eat better, sleep more, spend less time staring at the screen – the more the lizard brain will sense the danger of moving outside the comfort zone and it will freeze, fight or flee.

So what to do? During a Yoga for Writers course online I was asked to do a specific yoga sequence every day, then sit down to write for a limited amount of time. The yoga sequence was only twenty minutes long, which I usually consider too short a practice. Still, I decided to give this a try. We all know what happened. Yes, I stuck to it. Because it was a manageable amount of time, feasible and not too menacing. It didn't require that I badger myself into doing it. The more I did it, the more I enjoyed it, because it was not too much, yet just enough. Even now that the course has ended, I keep sticking to the twenty minutes. I even usually end up practicing longer, but I can always start out by telling myself: Only 20 minutes, that's all you have to do. No biggie. I find that I haven't taken so much pleasure (yes, pleasure!) in my self-practice for a long time. It is just a little moment of tuning in and being present with my own breath and body. I put a little bit of distance between myself and the every day hassle. And I no longer feel like I'm standing next to myself with a horsewhip.

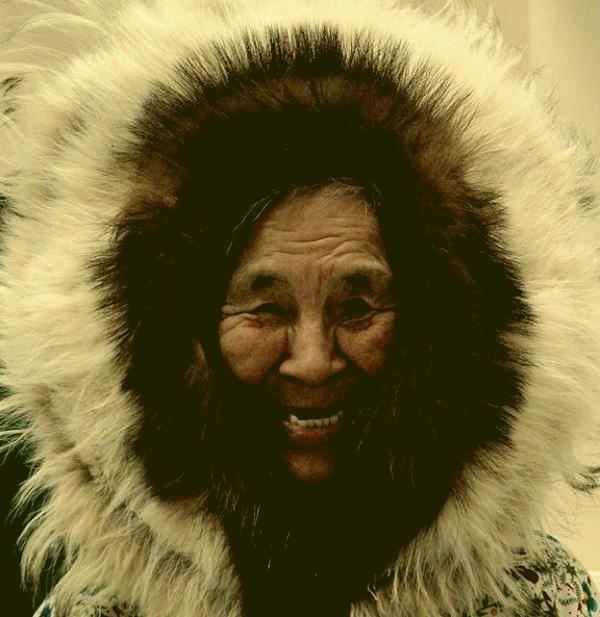

I remember someone once told me that the Inuit eat many little portions of food every day because it helps them stay warm. This is what this new approach reminds me of: one little portion every day to keep you going, adding up to many over the course of a week or a month. I've even started to call it my Eskimo strategy.

Many little portions eventually make up a plentiful nourishing meal. They are not to be sneered at for being small. Small is smart. It is not too much in one go, it is much more digestible and easier to metabolise that way. You never go hungry, but you are also never too sluggish from overeating.

It is simple, yet revolutionary.

No comments.